Aztec Empire

Aztec Society, Religion, and Culture (Overview)

Codex Cospi calendar

The Aztec people of Mexico have often been portrayed as a war-loving people, notable for their practice of human sacrifice. The Aztecs, however, also possessed a complex, multilayered society with a sophisticated economy and history steeped in rich mythology.

The Migration Legend

|

| Founding of Tenochtitlán |

Aztec war god, told the Aztec people that a divine sign would guide them to their new homeland. After hundreds of years of wandering, the Aztec came into the Valley of Mexico and found the sign—an eagle perched atop a cactus.

Originally a tribal band of nomads known as the Mexica, the ancestors of the Aztec probably lived in the northernmost region of present-day Mexico. Scholars have not been able to pinpoint exactly where they came from, but the Aztecs described their homeland as a place called Aztlán, which may have been purely mythical. Sometime during the 12th century AD, the Mexica began moving southward toward present-day Mexico City. The Aztec told the story of their migration in a legend. According to the legend, Mexica priests, gathering with several other related tribes at a place called the “seven caves,” discovered an idol of the god Huitzilopochtli who said he would lead them to a new homeland. Huitzilopochtli led the people around the barren area of northern Mexico for several generations. Whenever he directed them to stop, the Mexica built homes, planted crops, built a temple to Huitzilopochtli, and worshipped him. Whenever Huitzilopochtli directed the people to move, they did so. Then, in the early 13th century, Huitzilopochtli brought the people to the valley of Mexico, but there was one problem: the valley was already settled by other tribes who wanted no part of the Mexica. In addition, there was little unsettled land left, so the tribe continued to wander. Huitzilopochtli then told them to look for a divine sign—an eagle perched atop a cactus—that would indicate the location of their long-promised new home.

|

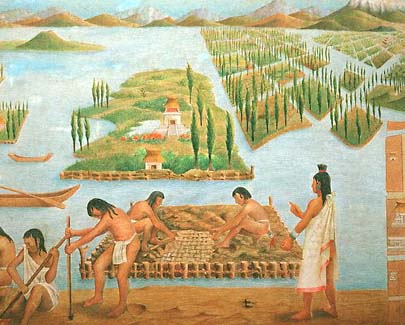

| Aztec gardens (chinampas) |

Depiction of the floating gardens (chinampas) of Tenochtitlán. The city of Tenochtitlán was built on an island, and the Aztecs cultivated year-round gardens along the banks of the island.

Seen as squatters—and extremely aggressive squatters, at that—the Mexica were chased by local peoples onto an island in the middle of Lake Texcoco. It was on that island where they finally saw the divine sign. This new island home eventually became the site of their capital city, Tenochtitlán. The island was not the most hospitable place to settle as it lacked arable land for growing food. However, it did offer abundant seafood and aquatic birds, as well as a ready-made transportation system for trade with coastal areas. The Mexica learned from their neighbors to create chinampas, which were floating crop fields created by dredging up mud from the lake floor, anchored into place by planting fast-growing reeds around the perimeter. With chinampas and the lake providing food and water transportation for conducting trade, the Mexica prospered, made alliances with their mainland neighbors, and selected a king or “speaker” within about 100 years of their arrival at Tenochtitlán. That political change was the starting point of the Aztec Empire. Society at the Height of the Empire

|

| Tenochtitlán |

Sixteenth-century illustration of Tenochtitlán, probably based on a sketch in Hernando Cortes’s book of 1524. British Museum.

By the late 1400s, expansion of the empire and tribute from conquered states combined with local productivity to bring great prosperity to the Aztecs. The vast territory to be administered called for a large bureaucracy, and the development of urban Tenochtitlán caused Aztec society to develop multiple classes. At the top of the social hierarchy was the king. He was assisted by a great staff of professional administrators and advisers, all of noble birth, who formed the highest class. That group lived in government housing and paid no taxes. Secondly, there were hereditary nobles who owned land that was worked by commoners. Nobles could be officers in the military, priests, diplomats, tax collectors, or hold other government positions. While enjoying a lavish lifestyle and possessing large estates, the nobles also worked hard for the empire. Following the nobles were two unique classes. The first included such master craftsmen as goldsmiths, sculptors, and lapidaries, who were highly respected though not especially rich. Accompanying them in rank were the pochteca, or long-distance merchants, who conducted lengthy trading missions and supplied the empire with luxuries, becoming extremely rich as a result. Both craftsmen and merchants lived in their own neighborhoods with local leaders and rules governing their profession, which was hereditary. In that respect, the two classes were similar to guilds in Europe during the Middle Ages. The largest part of the population, the commoners, worked the land belonging to their kinship groups, paid taxes, traded in the markets, owned homes, and were citizens. However, they could also be drafted to work on public projects. Peasants worked as tenant farmers, household servants, and soldiers. Although technically free, they were not considered citizens and had limited rights. Slaves, who were often used as human sacrifices, and indentured servants were at the very bottom of Aztec society. All men owed some military service to the king.

|

| Aztec skull rack (Tenochtitlán) |

Such skull racks as this one from the Aztec ruins at Tenochtitlán are found at the sites of many ancient Mesoamerican civilizations. The display of hundreds of stucco skulls is thought to symbolize the heads of decapitated captives.

Everyday Life Aztecs believed intensely that everyone must follow the path of their divinely appointed role in order to maintain order in the universe. There was, however, some limited opportunity to move up in the world. Religious schools for the training of priests and government administrators were open to children of nobles, craftsmen, the pochteca, and in some cases, even to commoners. Commoners could also be promoted as a result of military deeds and by capturing prisoners. The importance of maintaining the status quo was stressed from the moment an Aztec baby was born. A birth called for several days of celebration, religious rituals, visits from relatives, and numerous speeches instructing the baby about his or her role in life. A boy would be a warrior and follow in his father’s footsteps. A girl would be a housewife and mother. Such instructions were repeated many times in the form of lectures and stories throughout a child’s life. Training for adult life began with small household chores assigned to children as young as three. Somewhere between the ages of six and 12, both boys and girls went to school (though separately), where they were trained for their adult roles in society. There were different schools for the upper classes and for commoners. Discipline both at home and at a school was strict and harsh.

|

| Page from Aztec land record |

A page from an Aztec land record titled Fragmento de las Mujeres, about 1575. An Aztec home was simple; those belonging to nobles were bigger and of better quality, but all were sparse. Everyone rose from their sleeping mats before dawn. After bathing, the men went to work, returning at midday for a simple meal eaten separately from their wives and children. Commoners ate mainly corn porridge and vegetables, while the rich had more variety, including cacao (cocoa). Everyone worked hard, as was their religious and political duty, but there were also many forms of entertainment. The ritual calendar called for numerous religious events and games. The Aztec also played board games and enjoyed gambling. On market day, which took place several times a week in large cities, anyone could go to buy, sell, and trade. Thanks to the pochteca, every kind of food and luxury product was available, as were building materials, livestock, and medicines. One could even get a shave and sit down to a good meal before returning home.

Linda Unger

MLA:

Unger, Linda. “Aztec Society, Religion, and Culture (Overview).” The American Mosaic: The Latino American Experience. ABC-CLIO, 2011. Web. 28 Mar. 2011.

Email ID: 5663